Get the latest climate technology news directly to your inbox.

Report: How to scale frontier climate tech

McKinsey found that existing technologies could bring 90% of needed emissions reductions — but it’s time to invest in scaling them up.

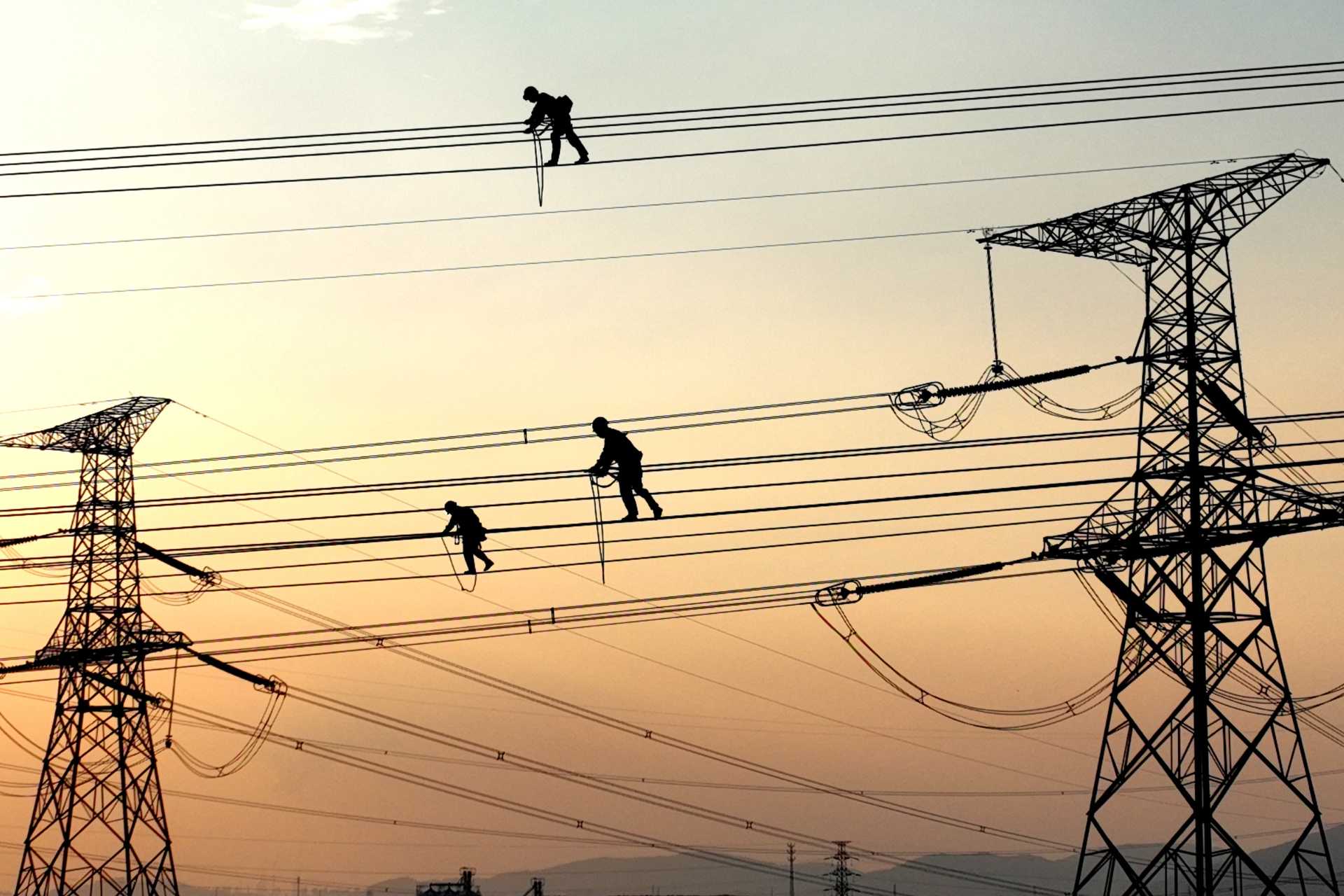

Photo credit: Ina Fassbender / AFP via Getty Images

Photo credit: Ina Fassbender / AFP via Getty Images

It is unlikely that some yet-to-be-invented technology will be the energy transition’s silver bullet. And, in fact, we probably won’t need it to be.

According to a recent report from McKinsey, climate technologies that already exist have the potential to reduce global emissions by up to 90% if deployed at scale. The catch? Many of them are at such early stages of development that their current impact on emissions is negligible — and their future potential remains uncertain.

The report, which is a preview of a deep dive to be published in 2024, found that climatetech investments need to grow by about 10% annually and reach roughly $2 trillion by 2030 to spur innovation and reduce costs to the extent needed to reach commercial viability. And it began to map out what needs to be done, practically speaking, to scale them.

McKinsey divided climate technologies into 12 categories, including renewables, batteries, energy storage, batteries, hydrogen, and engineered carbon removals. The analysis found that just two types — renewables and electric vehicles, the two that have already been the face of so much climatetech progress so far — are on track to cost parity by 2030 in much of the world without additional policy support.

There is no guarantee, however, that the other 10 technologies evaluated will achieve the cost reductions needed to scale up commercially in that time. Getting there will require two essential drivers: spending on innovation, and achieving economies of scale through industrialization.

Once a technology has matured, cost reduction tends to happen via scaling up supply chains and “manufacturing in lockstep with deployment and customer demand,” the report found.

McKinsey cited alkaline electrolyzers, a necessary input to achieve the growth needed for green hydrogen, as an example that is currently navigating this stage. The electrolyzers have essentially proven their efficacy, but costs remain high. Accordingly, manufacturers are focused on industrializing production and project development to get costs down by more than 60% by 2025.

The report also highlights three priorities to overcome challenges to full-scale deployment: improving and scaling supply chains and support infrastructure; embracing capital reallocation and financing structures; and tackling system-wide bottlenecks.

While just a few companies now control the supply chains for components needed to scale up frontier tech, things are beginning to change. The bulk of the funds provided by both the Inflation Reduction Act and the European Union’s Green Deal Industrial Plan are geared toward manufacturing, which means the market is ripe for new players.

“Companies that can innovate and scale rapidly while pursuing progress on cost reductions could be setting themselves up for exponential growth,” the report said, though it noted that this process is complicated by the fact that so many technologies rely on the same resources (as well as the same build-out of renewables).

Meanwhile, though investor interest in supporting climatetech has experienced a recent boom, the financing environment as 2023 wanes is harder than it could be. Getting nascent climatetech off the ground tends to be more capital-intensive than in other sectors that venture capitalists tend to patronize (such as software), and interest rate hikes are making things more difficult.

McKinsey recommended “a different approach to financing, one tailored to the new characteristics of climate technologies, including the unproven nature of immature technologies and sometimes steep up-front costs.” This could include mechanisms like contracts for difference, production tax credits, and concessionary loans, ideally in combination with the work of industrial venture capital funds like Breakthrough Energy Ventures.

Finally, the report highlighted the urgency of addressing the physical barriers standing in the way of scale for many of these technologies. For instance, McKinsey recommended investment in the grid, noting that the costs of “extending and strengthening electricity transmission and distribution” will likely represent 45% of total energy system capital costs in the 2030s and 2040s. Meanwhile, alleviating permitting delays and regulatory uncertainties would have wide-ranging benefits as well.

.jpg)